Story about a time of identity crisis and attachment anxiety

“In college, sometimes you just have to agree to disagree.” When I first heard this said in a college send away gathering, there was something jarring and bizarre about it that was difficult for me to process. As if a coded inference to a looming but imaginary danger, I found it to be logically nonsensical for why it needed to be said, yet so oddly disturbing, that I found myself reaching for a silent objection as I sat and listened to the speech. “What specifically, do you mean to agree to disagree? And if a common foothold has been established, what bars you from further discussion to reach a mutual understanding?” But before I could fully hit pause on my own musing, a few hands were already laid on my back. The speech is over, and now is the part where I should receive the blessings from my elders and be prepared to be spiritually strengthened in faith.

It is the time to pray.

As the murmured voices began to echo around me, I involuntarily lowered my head and stared blankly into the orderly woven carpet. All I could think of was the blatant inconsistency lying in that sentence.

Though I was told beforehand the send away was just going to be a small, light hearted gathering at the pastor’s house, with the few graduated young adults sharing the challenges and growth to their faith in college, the whole thing felt like a serious but unneeded ritual, as if a cult that came together solely for the purpose of reinstating an already established identity, that for some reasons had to be done. It was not that I could not foresee meeting people that came from different backgrounds; I mean, isn’t that supposedly the great appeal of the college experience anyways? To meet new people and learn new things. But given the scope of Christian belief, this oxymoronic suggestion to just “agree to disagree,” for something as notionally public as God, only seems wrong, as a dissent only for the sake of dissent would be equivalent to a willful ignorance to something as obvious as the existence of the physical law. Either God exists, and its basic nature is what Christians or at least what the other monotheistic religions claim it to be, or it doesn’t, for God has to be discussed in the same way as a proposition of knowledge, and for that matter, the objective truth. The more I entertained and twirled with this idea inside my head, the more confused and annoyed I grew, as I quickened my pace towards my car to quell the brewing uneasiness. Beneath the apparent ludicrosity in the suggestion seemingly lies a passive tone for protecting something fragile, that if not carefully tended against the surrounding darkness and indifference of the world, quickly wilts and dissipates into nothing. A cowering yield of the absolute truth.

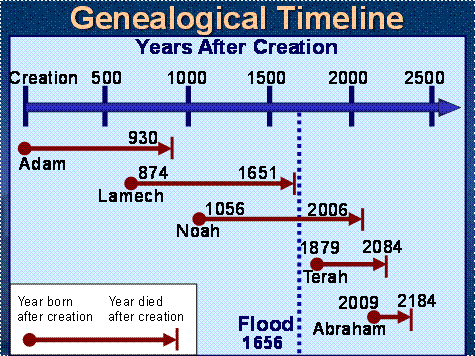

For as far as I can remember, my life has always been deeply intertwined with Christianity and its evangelical community, from the informal, underground house churches while in China to the large Southern Baptist church (where our little Chinese segment is winged under) after I moved to Charlotte. And having grown up as a Christian, there has always been a rather convergent outlook of humanity that gave a cohesive purpose to all communal activities, which is that one day, all people, whether living or dead, will be in union and stand before the judgment of God for going into heaven or hell. And this did not just come out of thin air, but from the authority granted by the canonical past laid out in the Bible, where it began with Adam and Eve’s fall from grace in the garden of eden for the entrance of sin, followed by the repeated rises and falls of the Israelites from their rebellion against God. And through their tribulation, the quiet and steadfast waiting for the Messiah was fulfilled in the coming of Jesus, who brought grace not just to the descent of the chosen tribes of Israel but to all humanity by his sacrifice on the cross. He was raised on the third day, thereby proving himself to be the son of God who conquered death, the ultimate price of sin. And this act of grace bears great significance, as now salvation in the coming judgment is determined not by the legalistic observances to the sacrificial rituals of the past, but by the personal faith in Jesus, that in virtue of his death and resurrection the last separation between mankind and God is mended. And unto those final days, it is the duty of the believers to profess the Gospel to those who have yet to receive, as it is the only reciprocation most apt of the love that Jesus has demonstrated. It is the firm belief in such universality and historical continuity of the Bible that powered the minds behind the various kinds of evangelical efforts: the fervent waves of revivalism, the routine programs of missionary outreach, or quite simply, the Friday youth groups about how to effectively share the gospel to our non-believers friends.

And this was what Christianity is all about under my impression, a set of unbending truths that are not only timeless, but also fundamentally normative in nature, as the realization of such truths is also a call for action on the believers’ end to bring forth the singular purpose for humanity as architected by God. But despite growing up with this framework and having my fair share of religious experiences, where I would vaguely feel a notional presence of God in the midst of my prayer and a connection with him that was both calming and deeply moving, the validity of the experience always came down to the correctness of the belief. A skepticism would invariably creep up afterwards, just in case to catch myself from any possible derailment from reality: is my encounter of God not just some psychological projection? Is what I felt in church not a mere fantasy that is explainable on the basis of some reinforced group psychology, but indicative of something that actually exists independently outside the projection itself? Those questionings that steadily accompanied my beliefs throughout childhood all changed by the arrival of apologetics. As a branch of theology, apologetics aims to defend the tenets of Christianity on intellectual grounds. It was first introduced to me in a series of systematic progression, where initially an abstract framework in the Platonic tradition is set up to frame the concept of God. Then from there, several reasoning steps are taken to progress from deism, to theism, and eventually to Christianity as commonly understood. In each step, the arguments drawn from a variety of domains, ranging from the humanities like philosophy and history to the sciences like physics and archeology, are used to build the layered foundation of the Christian belief system. With its permission for critical questioning, apologetics represented the holy grail of what I was searching for, the rational that is deeper than the religious. But it wasn’t just the intellectual appeal that attracted me. It was the sense of guaranteed assurance clear in its delivery that Christians are in fact the ones who hold the rational upperhand, and in a somewhat chauvinistic manner, it is uniquely Christianity that offers the most coherent worldview that ties together the moral and scientific advances. As a kid who just had the gate of knowledge cracked open in front of him for the first time by AP physics and calculus, all of this was exciting news.

But still an uncomfortable possibility of thoughtless detachment from the current state of the world lurked beneath my mind. The world does not seem to revolve around the center of my church beliefs. Secular humanism, serving as the alternative to the religious creeds that once gave definitive guidance to the moral questions of the Westerners, seems more and more attractive to a modern world outgrowing its dogmatic past. There is no consensus amongst scientists and philosophers on whether a cosmic ruler exists to govern behind the empirical reality, if there’s still major attention dedicated to it. Yet that does not stop the various institutions from their contributions to the repository of knowledge, for progress in the respective technicalities seems to be made without a distinct loyalty to any overarching principle other than science; the fruit of which bears a disruptive potency to all aspects of the public sphere. Indeed, science and technology, together with many other societal forces, have not only changed the way we come to see and experience the world, but they also seem to be best thriving under the institutions guaranteed by today’s secular society, where no particular religion asserts its authority to be the central order, and Christians coexist as equals amongst various other faith groups. Amidst my growing awareness of such pluralistic reality, I could vaguely feel the estrangement to it coming from a shared sense of Christian identity that stretched beyond the mere beliefs themselves. If I really thought back now on this resistance, however, collecting together the hints of the often preached moral decadence of the secular society, the counter cultural nature of the Gospel, the imperative for Christians to be the salt and light of the world, perhaps it has always been more apparent than what I initially realized. But in my collected self then, I thought of such rifts only as a product of flawed dialectics that can ultimately be settled by a common knowledge of certain foundational, unmistakable truths as promised by my notion of God, an all encompassing existence who surpasses my senses of cultural boundaries, and this should in turn ground the secret dread of identity. So to permit myself the freedom to properly understand any potential oppositions, I largely dismissed the whispered distrust of college’s secular liberalism as an overreaction that might have came from a place of genuine misunderstanding, for I wasn’t interested to guard my Christian identity only by a lazy and simplistic appeal to the metaphysical workings of Satan. If any, there has to be a better explanation, unbeknownst to me, for the existence of those contrary views today that did not just stem from arbitrary assumptions. So with all the perceivable paths leading to who I might become, I decided I would only proceed “scientifically”, with my beliefs laid out as discardable hypotheses in the trial of the common truth, and with God at its remote end. Surely, I thought of the intellectual approach as the only way to further any commitment to my beliefs in God. And whatever they turn out to be, they must be perfect and impenetrable to doubt, for God is perfection and rests upon an undoubtable ground fully objective to reason.

{{% quote type=“block” cite=“Matthew 7:7” %}} Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you {{% /quote %}}

Though I didn’t really have a specific methodology in mind, let alone a definitive criteria for what success might mean, I thought the best way to begin was to temporarily suspend my various beliefs, value judgements, and biases to try to understand any non-Christian perspectives, including those of my girlfriend who is agnostic. In particular, I wanted to start with testing the apologetics arguments I was familiar with as the entry point to see how well they are in persuading non-believers in reality. So as I entered college, I proceeded rather single-mindedly with this conviction, indulging myself heavily into the arena shitshow of atheist and theist on Youtube. Partly as a distraction to cope with my long distance relationship at the time, and partly as a means to retreat from the dizzying freedom of college, I spent most of my free time after class camping in the corner of Rams dining hall to binge on those debates (along with an unhealthy amount of league videos). And while there is a whole lot to say about the subject-matters themselves, as a plethora of them is available today on Youtube, it took me some time to realize how informal and ineffective those debates ultimately were for learning and progressing towards a personally satisfactory conclusion, at least for the many that I came across in the beginning. Whereas a debate between competent opponents in the academic setting is centered around a technical topic backed by the relevant research literature, the popular God debates begin with very broad theses, which leave much liberty to interpretation and path for argumentation. “Does the universe have a cause?”, “Is Evil compatible with an omnibenevolent God?”, “Is the Gospel historically reliable?”, “Does Evolution disprove Biblical Creation?”, etc. The debate format is more often counterproductive than not for the extensively scoped topics, as communication has to resort to general statements, which are charged with far reaching emphases that neither side cedes in order to preserve the integrity of the arguments. But when objections do collide in coming to cite specialized knowledge, it becomes difficult as a layman viewer to make sense of the actual point of contention, as it is hard to distinguish factual statements and their valid extrapolations from mere assertions; many such assertions are hard to connect from the disjointed responses and end up unchallenged within the time limit given to the presenters’ segments. As such, meaningful disagreements are buried few and far between and can hardly be converged upon within the limited time segment. Nevertheless, a casual viewer like myself would still conceive a supposed “winner.” But rather than arriving so by fully digesting all the points made and fairly assessing them by the use of some technical procedure, it is easily skewed by psychological factors that cater to the particular side of the audience, such as the speaker’s rhetorical style, showmanship, body language, or general likeability. At the end, it is not so much the argument’s conclusion that is getting sold but an impression, which goes on to live for far longer.

YEC & Fundamentalism

So as I sat in the dining hall, scrolling through all the comments and the back and forth retorts, I began to question the very efficacy that the apologetic enterprise had promised, whether the arguments themselves really bear the intended general and unilateral effect in persuading the nonbelievers. There are simply too many degrees of freedom for a focused discussion to those topics, and I was beginning to grow wary of the polemical rhetoric hidden in certain apologist’s presentations, which increasingly left me pondering more about the things that were left unarticulated or got quietly swept under the rug. But all of this was not to say that watching debates and peeking a bit into the weeds of debate were in any sense “useless” of an endeavor, nor that they failed to ever influence or even upset my own pattern of thoughts back then. Perhaps what the most lasting impact this exercise had for me, beyond just engaging with the many opposing viewpoints, was it made the first slim crack in the apparent uniformity I assumed to be behind the “biblical worldview,” as I began to notice the many subtle and thorny differences in the specific beliefs amongst its adherents, including those of my own. In particular, I became extremely troubled and yet intrigued by the fundamentalist strand of Protestantism, which was first introduced to me through the debate between Bill Nye and Ken Ham. For context, fundamentalism, as a biblical hermeneutic (interpretive) approach, generally means taking a literal as well as an inerrant view of the Bible. That is, whenever applicable, what the Bible says is what it means denotatively, particularly to claims about historical and geographical details (literalism), and adopting those claims would lead to accurate beliefs about reality (inerrancy). In essence, it treats the entire Bible as a book consisting of literal history, and the authors are divinely inspired to record it as is. Two particular conclusions, drawn by carefully tracing the events as documented in the Bible and following this interpretive process, are that humans, along with other life forms on earth, were created by God in a sequence of 7 24-hour days (Genesis 1-2), and the earth’s age is subsequently deduced to be only around 6,000 years. Together this formulates the basis of a particular version of creationism commonly referred to as young earth creationism (YEC), which rejects the standard Darwinian model that places the evolutionary process occurring over a long period of time. As a staunch adherent of YEC, Ken Ham went into great lengths in the debate to deny the validity of reconstructing the past using the laws of nature and dating methods, while affirming the creation account with the literal interpretation of the Genesis verses. So instead of descending from a single common ancestor, creatures already start off being created into different “kinds” (Genesis 1:21). Instead of a series of species extinction and emergence, there is a single global catastrophic flood that wiped the face of the earth as a result of mankind’s disobedience (Genesis 6:5). In the response, Bill Nye goes to show, along with a few back-of-the-envelope calculations, how species variation has to accelerate significantly in the hypothetical span of 6000 years to account for the biodiversity we observe today, fossil records excavated in Grand Canyon do not match what one would predict from the event of a global deluge, et al. Although I had a few rudimentary questions regarding the evolution stuff I was learning in highschool, and the answer given to me was to not take the Genesis’ creation story literally but instead opt to be skeptical towards “macroevolution”, it was troubling, in the particular case of YEC, to see both how narrow and far fetched one can get from interpreting the Bible this way from the full complexity of nature we have only begun to grasp. The more troubling thought surfacing, however, isn’t exactly who and how one is right about evolution or creationism, as my formal literacy in Biology barely cuts past the highschool level. It is how one’s interpretation of the text in general, together guided by the surrounding communal attitude, feels compelled to be adjusted to stay consistent with the progressing sophistication of data collection means and overall scientific understanding to fit all the pieces together, when there is nothing inherent in the text itself to foresee nor demand this shift in interpretation. Yet at the same time, it is the beliefs one accumulates from reading and plainly interpreting the passages that I took to be the building blocks for a Christian worldview: the first fall is predicated upon the reality of the creation story and the existence of Adam and Eve, Noah’s ark upon the global flood, Exodus upon the Jews’ captivity in Egypt, etc. As I was following the vein of creation science to its various other historical tangents, I found that many earlier believers certainly have no qualms with rationalizing the Biblical accounts literally, with beliefs in solid firmament, flat earth, geocentrism, or any other superseded theories favored at the time that were also paired with Biblical accounts as a confirmation. Today, the instinct for the same inerrancy doctrine very much persists (or to at least maximally accommodate it), albeit via rather specific strategies. For Biblical creation alone, this could mean pressing on arguments for irreducible/specified complexity as an Intelligent Design proponent or contesting fossil records and dating methods as a YEC. But with my naive thought process at the time, I firmly believed and expected that the inerrant words of God have always held the same, “objective”, and literal meaning that is in harmony and set to be confirmed by the modern scientific findings. But in reality, it seems rather the other way around, with believers adjusting the disparate interpretive means and response mechanism, and with no trace of God found synchronizing all the dissonant beliefs.

Synopsis of YEC history

Looking back, I had a particular fixation on fundamentalism, perhaps because I was very much one myself. Or rather, I did not see a reason to not be one in the first place and share the same straightforward expectation of a fundamentalist, especially considering that the Biblical God obviously wants people to believe in him and tying the stakes of deciphering the proper meaning and way to act with eternal punishment in hell. Indeed, my problem with fundamentalism is by no means anything new and untrodden, and there are good responses that instead emphasize Biblical infallibility from both contemporary and antique sources. But it still stuck with me a knotty problem of language lacking a clear boundary. However one’s version of Christianity is like and vague as it be, there are still certain fundamental beliefs drawn from engaging with the verses or with all the secondary presentations (pastors, videos, small groups, etc.). The judgment point just seems to fluctuate between what we believe the text to proclaim literally about actual history (i.e. 7 day creation or Jesus’ bodily resurrection) and what we believe to be the hidden intention of the divine (i.e. symbolic relation to how the stories all fit with the salvation plan of Christ). Admittedly at the time, the two made little differences to me. And from consuming all the debate videos and doing my little informal side research with Google, I found myself becoming both more interested in the historical side of Christianity as well as more aware of my own ignorance about the texts. So with the aim to learn more and verify the historicity of the Biblical figures and events, I largely continued with the momentum as somewhat of a fundamentalist, except taking the text as only literal data points to be studied.

Textual Criticism

As I was beginning this “fact checking” journey, it was Bart Ehrman who was the first guide that introduced me to a historical-critical approach to the Bible. I first found out about Ehrman from a theodicy debate between him and D’Souza. A New Testament scholar and professor at UNC, Ehrman similarly began as a fundamentalist who believed the Bible as the inerrant and inspired words of God, but he gradually became disillusioned from this position as a result of his scholarly work as a textual critic, and he eventually turned away from his Christian belief system from his reflection on the problem of evil/suffering over the years. Ehrman is quite the popular skeptic and target of scholars in the conservative Christian circle, with a whole website dedicated to refuting his arguments and critics challenging his scholarship and even integrity, but his proximity to my academic environment, evident talent as a teacher, and candidness to his personal journey still greatly captivated me. So as a gateway to my study, I picked up one of his best sellers, Misquoting Jesus, which was a layman’s introduction to the transmission story behind the New Testament (NT) and how textual criticism applies to its study. And from it (with Google-fu) I first learnt about the few basic historical backgrounds1 surrounding the text and the early Christians:

(Note: below gets bit into the details of NT history to explain part of my thought process, feel free to skip forward)

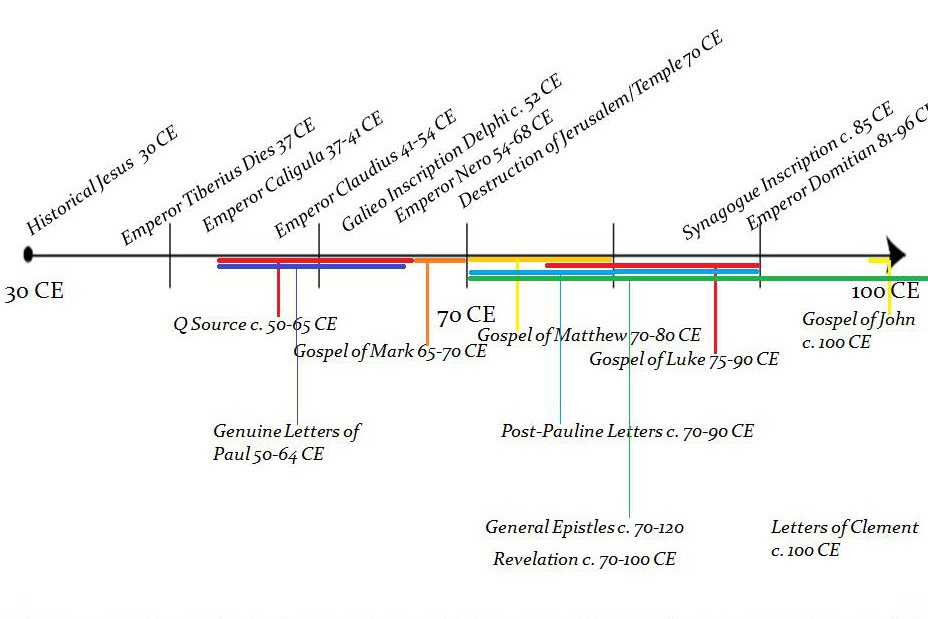

- The Gospels (Mark, Matthew, Luke and John) detailing Jesus’ life were written at least decades after Jesus’ death ~30 CE.

- The earliest, Mark is dated to around ~70 CE by most scholars2. (excellent post for explaining textual dating of the gospels, which unfortunately is not a very precise process).

- Other gospels or sayings about Jesus were written around the time; some are lost (i.e. the hypothetical Q source); some did not make it into the canon, such as the Gnostic gospels found in the Nag Hammadi library:

- Gospel of Thomas, allegedly by Jesus’ brother Judas Thomas

- Gospel of Philip, allegedly by Jesus’ disciple Philip

- Gospel of Mary, allegedly by Jesus’ female companion Mary Magdalene

- Correspondingly there were other groups of Jesus’ believers with fundamentally different views of him and his teachings, and they accepted different gospels (i.e. apocryphal). Those groups were eventually deemed heretical by the Proto-Orthodox Christian voices represented by the Church Fathers, to state a few:

- Marcionites (followers of Marcion), believed that the God of Jesus is a fundamentally different God from the wrathful, vengeful Jewish creator God. They accept only a form of Luke

- A group of Gnostics called the Valentinians accepted only John

- Ebionites, the Jewish Christians who held to the ongoing validity of the Mosaic Laws, used only Matthew

- Certain groups who argued that Jesus was not really the Christ accepted only Mark

- The formation of the current NT canon is actually quite a long process. The first (surviving) attestation of the whole 27 books as the books of NT was by Athanasius in 367 C.E., almost 300 years after the first Pauline letters and gospels in the NT were written

- The first attestation of the 4 gospels by name is by Irenaus around 180 C.E.

Those were just the few things that most stood out to me at the time when reading Ehrman’s rough sketch of the early Christians’ environment. Like its predecessor of Judaism, Christianity began as a very bookish religion at its conception, with its identity shaped by the wide range of literature circulated in Christian communities: gospels (not just the canonical ones), missionary acts of apostles, epistles to churches, accounts of martyrdom, tractates against heretics, expositions of scription, etc. However, neither printing press nor publishing houses for mass production exist at the time, so those literature were made available by scribes manually copying the text, and they were distributed to be read aloud by the few literate members during church service (since mass literacy was also not a thing, and most early Christians were uneducated, illiterate members of the lower social class).

The main crux of the book is directed to the textual transmission of the collated NT. The reality of this process, however, is rather tricky to say the least: once a copy is made, it is basically out of the original author and the previous scribe’s control. And due to the manual nature of the practice and the absence of any centralized copyright law enforcement in antiquity, variations were gradually introduced into the text. Later scribes in different geographical areas would then use those copies to make copies; those copies of copies of copies then get passed on, eventually resulting in differing manuscripts and separate streams of textual traditions that produced them. Especially for the earlier manuscripts before the 4th century, when scriptorium and the professional scribe class had not yet emerged in the church, variations occurred more frequently because the scribes were by and large amateurs, and the copying practices were more wild and less controlled.

The majority of NT manuscripts textual critic scholars inherit today are Greek and Latin manuscripts that are centuries removed from the time the texts were originally written in, and the general pattern is that the closer one moves up the timeline, the fewer manuscripts and more fragmentary they are (chart of fragments’ dating). To quote Dan Wallace, another prominent textual critic from an evangelical conservative background and Ehrman’s debate opponent:

We have today as many as a dozen manuscripts from the second century, sixty-four from the third, and forty-eight from the fourth. That’s a total of 124 manuscripts within 300 years of the composition of the New Testament. Most of these are fragmentary, but collectively, the whole New Testament text is found in them multiple times.

Now the vast majority of the variations in the manuscripts stacked together across time do not affect the reading whatsoever, such as unintentional copying mistakes, spelling/grammatical errors, or alternative word arrangements in Greek. But some variations are slight word and arrangement changes that do appear intentional and alter the meaning subtly; the motivation behind those changes varies widely: “correction” of the variations that scribes detected with other manuscripts they retained (which may well be actually inaccurate in respect to the original autograph3), harmonization amongst gospels’ narratives, hints of the scribe’s own inclinations in the raging theological debates at the time, etc. Some are sections of entirely new additions not found in any other older manuscripts. Ehrman goes into each of those cases a lot more in depth in the book, but I’ll just summarize the more notable ones to me that textual scholars determined to likely have deviated from the original autograph:

- Mark 1:41, the compassionate Jesus healing the leper. (Angry in the early manuscripts)

- 1 John 5:8, the explicit affirmation of the trinity doctrine. (Not in the early manuscripts)

- John 7:53-8:12, story of Jesus forgiving the woman taken in adultery. (Not in the early manuscripts)

- Mark 16:9-20, the long ending section of Mark containing Jesus’ post-resurrection appearance to the disciples and preaching of snake handling and faith healing as markers of the saved. (Not in the early manuscripts)

There are obviously a lot more narrative vacuums to unpack (i.e. about the manuscripts themselves or additional sources like church leaders’ quotes about them), and many of the differences require actually parsing the manuscripts in their original languages to appreciate (i.e. Greek, Coptic, Latin, etc.). After all, textual criticism is an entire sub-field of history and a well-developed one for the NT. And despite the rather sensationalist title, much of what the book discusses are largely consensus in the field for the “correct readings” and the problems for the unsettled ones, with Ehrman’s own extrapolations explicitly stated. So what is the conclusion? Is the NT text we have reliable recordings of the original text? Does knowing all the changes challenge the traditional Christian beliefs?

History behind the text

After re-reading the book and revisiting this topic again, to me it certainly does not advocate for conspiracy in the copying practice at large nor complete skepticism in what scholars have managed to recover4, though the variations with contested authorship are certainly added dimensions to the heated debates about Jesus, Paul, and apostles. And as readily acknowledged by Ehrman in the book and debates about this topic, most variations do not alter the essential beliefs5 of Christianity. The NT is significantly more well preserved with the copious amount of surviving records in comparison to other ancient literature (it is the holy text of one of the world’s most dominant state religions after all); the NT translations that modern readers have today are based on critical texts, with consensus of transmission errors appended as exegetical footnotes, and other quantitative studies provide an optimistic summary on the limited impact of those variations. All less the reasons to abandon bible study based on such skepticism.

But this book still left a deep mark on me for a multitude of reasons. For one, this is supposedly God’s text, text intended by God to reveal about him (and his change of plans from the Old to the New Covenant), not Iliad or any classical literature, nor any other historical documents like some emperor’s memoirs. People had bet their practices from arguing the exact meaning lying in the vague sentences, often with differing interpretations casted as heresies. And yet the story of the corpus itself, its formation and changes, seems to bear more a distinctive trademark of the human hands than divine guidance, with some interpolation being the result of political pressure. After stepping out of the philosophical and young earth arguments, this was a rather odd change of expectation for me in the degree of God’s involvement for humans and the natural world, where God is argued to cause space time to exist, to fine tune the universe’s fundamental parameters, to even accelerate plate tectonics. Or in the Old Testament, God is even more alert with smiting Israelites for accidentally defiling his covenant by catching it from falling, yet silent on scribes altering his holy text that certainly call for skepticism. It certainly opened up a flood gate of questions for me: now that I know there to be variations, both textual variations from the transmission process and the narrative variations amongst the different gospels as touched upon by Ehrman, why not peel back further to postulate why they made it there? Were the early scribes and gospel writers hearing stories circulating around their communities, which pushes the problem back to the reliability of oral tradition? What about the intentions of the anonymous gospel authors and their conditions? Were they attempting to record history as factually as possible (up to the standard of modernists), or was there a co-mingling between recording brute historical events and writing into the theological views/expectations informed by the authors’ Jewish/Hellenistic cultural background (i.e. filling in blanks left from the book of Daniels)? What were the other presuppositions of Christians about the world back then and contemporary followers of other pagan religions? Why were there pseudonymous practices and forgeries in Paul and Peter’s name? Do the different groups of Gnostics, Ebionites just share fundamentally different interpretive frameworks of Jesus from their sources and communities, or to the traditional answer, the church fathers are defending against the Apostolic tradition that faithfully preserve Jesus’ life and sayings, you know, the true, historical Jesus? Besides all those questions, it was perhaps this overall developmental aspect of the beliefs that most surprised me, where the Christian identity/ies was developed from not just external pressure but also conflicts amongst “Christians”. And even before the vast array of denominations in existence today, the diversity of beliefs regarding Jesus was already baked into the very beginning of Christianity (good list of them beside the two mentioned prior). The notion of canonization seems to have risen naturally from this heterogeneous environment, which really seems to boil down to a selection effort based on authority:

- Selection of the right books and the right sayings (of Jesus, Paul, and so forth) amongst wrong ones.

- Selection of right interpretations of those verses amongst wrong ones, which collectively forms a guiding theology (or vise versa)

- Selection of people having those interpretations as authority amongst wrong ones (i.e. wrong teachers).

What accompanies the selection effort is the emphasis of certain thoughts and representations of God from others. Perhaps in this latter broader sense, canonization never ceased being a thing for Christianity in practice. To take homosexuality as a modern example, in the more socially conservative congregation, Leviticus (18:22) and 1 Timothy (1:10) are the go-to passages to demonstrate it as a sin disapproved by God, perhaps paired with Christ’s salvation role centered on Matthew’s depiction as a fulfillment (and not abandonment) of the Jewish law (Matt 5:17). And needless to say, those focuses are heavily contested in the more socially liberal congregation.

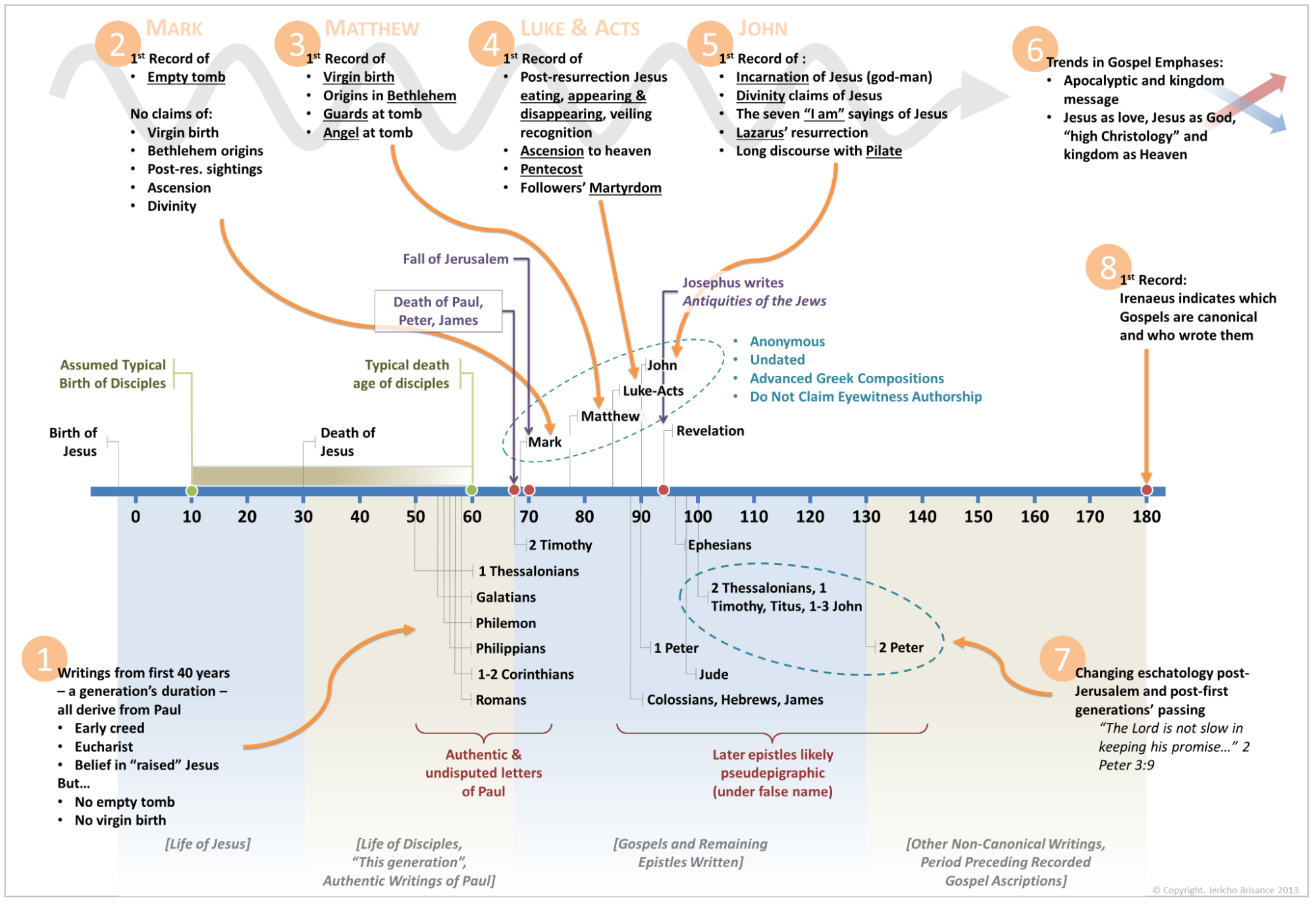

Common Gospel dating and surrounding events - Jacob J. Prahlow

Infographic illustrating some distinctions in Jesus’ narrative accounts - Jericho Brisance

But again, I knew none of those things before. I simply assumed that Christians have always conceived and talked to the same God, so being “Christian” has always been a unified group identity. Part of the reason for this, besides the rather homogenous culture of my Southern Baptist upbring, is that I have held to a rather monolithic view for the gospels and the Bible at large, where I already began with a set of preconceived notions of God before reading into text. Pastors, small group leaders, or I can simply cite back and forth verses from different books for reinforcement, without having a robust understanding of the numerous authors writing and living through history and taking the cues left from them. This is then further conditioned by doing the fragmentary readings paired alongside with sermon messages and having the modern set of Bible at my disposal ever since I was a kid. Like how textual scholars compare manuscripts and employ literary analysis to understand the differences, Ehrman introduced me to a comparative way of approaching the Bible: juxtaposing and reading different books side by side (the gospels and other books with similar themes), which instead of crafting our own ideological mega Gospel/Bible, does more justice to each authors’ own purposes at their own times. And this way of reading also reveals the Bible to me as less monolithic and uniform as I initially thought it to be.

So in many ways, this book influenced me for reasons far more than just knowledge of the textual variations. It was a catalyst for my already sprouting academic interest in Christianity and the world behind it, and it plunged me into doing more researches of other tangential topics turning up from the book, surrounding debates, and of course Google-fu: the Synoptic problem (i.e. concerning the literary dependence between Mark, Matthew, Luke - how the authors basically just copied each other for many narrative portions, with differences tracing to separate oral traditional sources), high-low Christology (i.e. concerning how Jesus is deified amongst different sects of Christians, when he started as a Galilean preacher for the impending kingdom of God), textual problems in the Old Testament, Biblical archeologies, etc. And beyond the Bible, it led me on a spree to read books about church history and the developing dogmas as Christianity becomes more and more organized, or the secular, explain-the-religions type books like Evolution of God that touch on the animism, monolatry roots in Jewish monotheism (i.e. shared traits of Canaanite gods like El with Yahweh), or Sapiens that talks about how humans are adept in using intersubjective imagination to achieve many powerful goals, such as the shared beliefs in abstract things like money, corporations, and God(s)/angels/demons. I signed up for history class of pre-modern Europe to learn more about the trajectory of Christianity into the middle ages, and I even influenced my girlfriend to take a class of early Christian history and bug her to tell me all about it. All of those things left a deep impression on me, because I was at an impressionable time. But much of the driving force behind this fervent quest was also a seething anger at how little the church had actually fairly talked about and prepared me for those things, without submitting to broad generalizations and omitting information irresponsibly. In my thoughts back on apologetics then, I realized what this subculture actually ends up prescribing to a kid like me was an overtly protective and defensive attitude towards perceived challenges or dissents, rather than a mindset of curiosity, charity, and honesty to understand things thoroughly first before immediate refutation. To be fair, this aspect of the apologetic persona may well be a reaction to the stream of militant atheists who should very much be accused of the same (which may in turn be a reaction to strands of fundamentalist arguments that are triggering in their own regards). But such a defensive attitude to protect one’s fundamental beliefs at all cost encourages a short circuit type of reasoning nevertheless, where once a differing position is sensed, one becomes a kind of fallacy police to try to spot any holes in the assertions, inferences, or other justifying reasons in trying to defeat the “enemy”. And if one part seems to fail, the entire opposing thesis has to go, concluding with tropes and catch phrases like “I don’t have enough faith to be an atheist”. The tendency to catch those informal fallacies sometimes rides on the shallowest interpretation of the conveyer’s point in an attempt to control the dialogue (for conversion), and it incentivizes a strategy to reject fast over listening earnestly, rather than the other way around. But despite becoming more aware of the toxicity and pitfall, I still carried the same attitude for a long, long time with me in learning, except I subconsciously rebelled and tried to do the opposite, for a counter-apologetics so to speak. The more nuances I learned in my books and classes, the more it contributed to this building of internal grudge. And for my fairly emotional/non-intj brain, this doesn’t help with information processing and understanding in the first place, nor does it help me in fairly assessing the bias of the authors that I was reading, which readily comes from the way one defines concepts, selects sources, and overall use of language. Who would have thought that learning things for a grudge is not a good thing.

2016 Election

Despite finding a church community and attending Bible studies, I was largely stuck in my own head with such seismic changes in understanding. But at the same time, the world around me was also shifting rapidly, faster than I could have it all figured out. In 2016, Donald Trump was elected president. For the predominantly liberal student body of UNC, this was an event akin to being swept by Duke basketball in the Final Four. I remember the day after the election, the whole campus had seemingly lost its usual vibrance, with students scurrying past each other in silence and a few proudly wearing their MAGA pride weaving in between. I would overhear chatters from classmates and coworkers about their reactions, and I would find articles and comments with people’s starkly different opinions. For the conservatives, this was a major victory to turn back the pages of liberal agenda put forth by 8 years of Obama administration, with a hope for an outsider like Trump to drain the swamp of elite oligarchs at Capital Hill. For the liberals (and never trumpers), Trump’s victory is an ominous sign, indicated by his nepotism, normalization of bully tactics, and similarities to past dictatorships. I remember feeling an odd sense of duality and misplacement going through it all, partially because 2016 was my first actual exposure to American politics, when I didn’t have many particularly compelling opinions, but also because in some ways, I identified as a soft, closet conservative in a hyperpolarized time. It’s not hard to understand this inclination about myself now, especially not for myself back in 2016. If college liberalism is narrowly associated with the drinking culture and openness to psychedelics (hence the social stereotypes), I was the awkward antithesis who preferred the control of sobriety and familiarity and tried to follow the teachings of the church. My family, parents and grandparents, though not the most stringently hierarchical, “respect your elders” type Chinese, nevertheless hold on to and inscribed me with the typical traditional values, especially when it comes to individual work ethics. Politically, I am more inclined with the ethos of the Republican tradition to respect procedural processes (though it is debatable whether this is something uniquely of Republicans, and very questionable whether Trump is one). Lastly, I was fresh out of a conservative southern church, baptized with pro-life arguments and a swaggering confidence in them. All of those things, in a very loose sense typed under a general caution to new changes and risks, would bend me closer to some association with conservatism. But in 2016, it wasn’t just those politics as usual. The election has caused quite a shake up amongst the peers of my college church, for the very fact that Trump’s success also rode on the support of an overwhelming majority of evangelical Christians. I remember following those enthusiastic voices rallying behind Trump, thanking God for giving us Trump, praying for God to bless Trump to do great things, and nodding along to his chant to stop the radical left mobs who want to take away your guns, your religious liberty, etc. I just couldn’t help but to sense something odd. You see, it wasn’t particularly about the conservative stances that were bothersome to me then, for people have the freedom to express their support and reasonings for whatever things they genuinely believe in. It’s rather how the concept of God is freely invoked in the overall political package of Christianity that is. To me, there was simply no necessary connection, if not any, between Christianity and the pro-gun, anti-immigration, anti-lgbtq, free market capitalism, and all various other things lumped together under the conservative umbrella. In fact, many of my Christian peers in college found those positions, altogether with Trump’s fiery delivery, to be offensive with the centrality of Christ, especially considering what is demonstrated by Jesus himself as depicted in the Bible. The very same son of God, who lowered himself to serve and be amongst the lame, the poor, and the weak, who preached to his followers to love your enemies and love thy neighbor as thyself, who challenged the sadducees’ obsession of law and etiquette, pronouncing that the law serves the man and not the other way around, is also transformed with the masculine undertone into the son of God who would permit your God-given rights to own guns, call for the just wars, protect the private enterprises/churches (for all government under the authority of men are evil), and whose name is to be preached militantly through the beacon of America. This mission also calls for a zealous defense against the domestic infiltration of Marxism/Socialism poisoning the minds of young people, as well as an overall urgency to reassert America as exclusively a Christian-nation at its root. Oh and btw, we should also elect the border wall, make the Mexicans pay for it, and tighten our immigration policy to only allow the good ones to come in, the educated, law-abiding, and “useful” immigrants. Peeling back each of these things, one can certainly massage the language and argue that they are consistent with a Christian, Bible centric worldview, perhaps citing more verses back and forth for justification. But it seems wholly fair to me to do the same and see the contrary as also support for the socially liberal causes: wouldn’t Jesus and the first Christians’ radical charity6 align with the support for the working class as championed by socialist thinkers, some of whom are Christians? Wouldn’t Jesus and the disciples’ care for the poor and minimalist focus on earthly wealth serve as a reminder to dial back the incredible consumerism and waste enabled by an unchecked capitalism? Wouldn’t the same spirit, prima facie at the least, move one to be sympathetic for universal healthcare as a positive right for the least of us, or does it stop at any degree of state involvement or at one’s wallet? Wouldn’t this obsession with guns, the mere presence of which incites aggression, ought to be curbed a little with the teachings of Jesus and Paul for non-violence and trust in the gentle Holy Spirit, especially after guns have enabled people to cause many tragedies beyond simple “thoughts and prayers” can address? The list can go on and on, and I was sensing a building schism in my immediate communities and the American Christian scene at large, a parallel support for separate political authorities citing the very same name. Yet instead of trying to make sense of this all as God working through different people for his grand plan, with liberal Christians being the fake Christians and with conservative Christians being the true Christians, with Obama being the enemy and Trump being the God favored, it all started to come apart as all the more arbitrary than that. Just this prioritization/pick and choosing of possible Christian beliefs, despite the stringent insistence of them being all founded upon the Truth in the Bible, seems in practice to be very much a natural byproduct of one’s subjective, limited outlook and experience in the world and historical period, which are intimately tied to the surrounding culture as constructed by one’s nationality, economic status, skin tone, gender, age, media consumption, family, social circle, etc, with religion mixing squarely in between. In my purely ideological quest for truth then, it was such indigenous aspect of Christianity that was particularly foreign to me, for how malleable “a faith guided by truth” is to cater to one’s tribal affiliation, for how this exclusive identity of Christianity was wielded primarily to demarcate in-group and out-group, with God invoked as a cheerleader all along to prop one up triumphantly and stomp down the other.

The actual reasons for the Republican coalition/identity backing behind Trump, blending together the Evangelical right, the laissez faire capitalists, the patriotic gun fanatics, the conspiracy theorists and the various other groups and sub-groups, are probably really complicated and historically multi-threaded, with the first two tracing back to Reagan and whatnot. But the marriage between Christians and Trump still left me then with a poor taste, especially coming off to me with a quid-bro-pro move behind it: give us conservative judges to push forward the pro traditional marriage/anti-lgbtq and the pro-life/anti-abortion policies to win the culture war, and we give you Trump, who we can simply overlook many other things and quietly reserve our what would Jesus do critiques (i.e. by shifting the framing language). It really affected me because for all the ambiguities surfacing in my studies and my attempted formalism to make sense of them as a Christian, the sheer force backing behind Trump made such a political statement seem as if it was the clear-cut, rational necessity to bring forth “God’s will”. That a living faith should also mean a vote for Trump as a step in this greater road to “God’s kingdom”. And as I read more into some of the conflicts, I found myself constantly coming back to a set of questions that simply were just never quenched:

Why should I pretend any of this as a devotion to God, for reasons that seem practically human and can be simply owned up as such?

Why should I justify the ego for a political belief with the mighty notion of God?

What exactly are the criterias that distinguish between a human motivated reason in politics from a God granted/inspired/bestowed/sealed one?

The typical pastoral answers for the latter come down to reading the Scripture and doing prayers to heed to God’s voice (in a way that’s not a self-fulfillment), yet before taking a step back to consider that Christianity is not the only belief system in the marketplace shared by all Americans, there are 66 books, 31,102 verses in a standard Christian Bible, a volume written, compiled, translated across thousands of years that described the conception and consciousness of God from the lens of Jews and a sect of early Christians (internally diverse in their own rights). It is situated squarely at their unique times and environments. Which verses and ideas to continue the focus on, and how to focus on them? So Americans in the 21st century can understand what God wants us to do with our lgbtq/muslim neighbors (enemies), with fake news, with big pharma, with data privacy, with debt crisis, with China/Russia, with climate change, etc? The irony didn’t fully settle for me from just trying to pair an ancient book with literally every issue coming up in modernity (as it is surely done), but pretending that a book alone is ever a fully “objective” source. For one, as a Catholic would argue, the text is not something self-interpreting, with contextual meaning just flying out of the sentences and the Holy Spirit delivering into every Christian and non-Christian’s mind reading. Because of the limited brain power/time/memory that an individual has, a separate human authority, however implicit, is almost always being appealed to in the process to make sense of the Bible. So just as the corporate media that the conservatives trash for bending the narratives, the very cultural monoliths of American Protestant Christianity are also propped by their own media and human authorities representing God first and foremost, sensing what they see as dangerous against the tradition and selecting the focus/interpretation for its congregation, in the process compressing and shoehorning verses into convenient abstractions for sell and consumption. Perhaps in this regard, the Bible is never a book in and of itself but has always tied to the world that the people and their community inhabited in, a world that gets subtly carried into the reading before the pages were turned open. And for any Christians reading the Bible as a continual practice of faith, it’s such tension between the dynamic world and the static text that makes the personal reading for navigation today easily a re-interpretation beyond the meaning encapsulated by the attention of the Biblical authors in their own environment, which many modern readers such as myself are hopelessly blind to begin with without formal training in the respective historical disciplines.

Christian Politics (the not happy ones)

Although the loaded school work quickly turned my focus past the election, this quasi nationalistic version of Christianity that I first felt in 2016 lingered in the back of my mind for a very long time. But from my later learnings I also came to see that this was not exactly a new phenomenon. Back then in Germany, in response to all the new human rights stuff coming out of French Enlightenment and the liberal sexual culture during the late Weimar Republic, there was a similar antagonism brewing amongst the conservative church congregants, for losing their grips on issues of traditional sexual morality and fear of forgoing the Gospel’s authority amongst the Gentiles. Unsurprisingly, this sentiment was leveraged effectively by the you-know-who in his rally, in which the source of blame was piled onto the Jews then, and the latter Postive Christian movement further built on this domestic anti-semitism to syntheisze Christianity with Nazi ideology/state. The German Christians is just one fairly modern example of God’s weaponry use for its in-group/out-group potency, where God was most manifestly tied with a modern nation-state, there are plenty more that I came to see in the long road paved by Christianity as an organized religion: Popes launching Crusades against the Muslims pagan enemies, citing war as a means to pay for one’s penance and display loyalty to God, Conquistadors massacring the natives heathens for gold and subjugating them into slavery, with the victories attributed as providence of God. On the softer missionary side, there are the state sponsored boarding schools for the forced assimilation of Natives, which removes young children from their ancestral home and couples Christian indoctrination as a means to erase the cultural lineage. Some of the violence is readily told in the Old Testament but glossed over or theologized into God’s unflinching justice, like the Canaanite conquest and massacre depicted in the book of Joshua with Yaweh’s seal of approval (that ironically may not have happened in the way described from the absence of strong archeological evidence). The weight of those things didn’t fully strike me until I read through some of the translated primary sources myself; and the increasing dissonance was not in what ways those Christians strayed from the “correct” set of teachings or ways of evangelism, but how much their particular ideation of God precisely made sense to them in those context, yet hardly at all for someone like me standing from the outset looking back to it.

Learning them all for the first time plagued me emotionally, thinking what really is the point of upholding a Christian identity if those could be the kinds of end products. On the other hand, intellectual questions continued to get generated as my focus swung from history back to the philosophy stuff in the likes of mind-body problem, conceptual ethics, language, knowledge, etc. In all the interconnected web of information, I found it harder and harder to fit every little piece together. And being true to my initial body of beliefs in (a particular version of) Christian God is implicitly committing to beliefs in many, many other things, none of which are practically doubt free. Yet this gap was a constantly growing one in between me and God, and eventually, I reached a point of implosion.

I was on a trip attending this student SDE summit program, and I remember that night there was a social scavenger hunt event, where I told the group I was with that I’d stay back from feeling really tired. I remember lying in the empty room, staring into the ceiling and mulling over my questions. I remember thinking to myself, perhaps thoroughly convinced then, that I was the only one in the world that truly loved and respected God, by believing in the unthinkable vastness behind this very abstract idea of God, even amidst my most intense doubts. Yet something about God that was real to me as a child before was slipping away like sand, and I was increasingly left with no structures to stand on. Indeed by my own standards of trial, hoping to establish the Christian God as an undoubtable foundation, an archimedean point to Christians and non-Christians alike, I have utterly failed, underestimating the complexity of the world and realizing the vanity of my childish hubris driving behind the ambition. But a real side of me was crawling out, suppressed by reason and insistence on an analytical mind, and I was slowly eaten away by a darkness within. Fully cognizant of the limitation to my knowledge and mental capacity to make sense of it all with my own power, I kneeled on the bed, sobbing and praying for clarity to those questions and ambiguities, pleading for God to speak past through the silence to me once again, for God to punish me for me to know if I or my methodology have strayed too far, for God to reveal distinctly and unambiguously to me as the God of Abraham, of Issac, of Jesus, of my peers, of my Mom, of what I believed in before, as he had did times and times before to others.

I wasn’t able to get back anything.

Footnotes

-

Want to be cautious with claiming “facts” here, as there are many camps of scholars and little universal consensus regarding specific claims around the historicity of the Gospel and Jesus. Scholarly consensus are handwaved sometimes in debate for the purpose of moving the conversations forward, but sometimes just as a lousy appeal to authority ↩

-

Another slippery phrase for the same reason as above. Some apologists from conservative Evangelical camp, like Warner Wallace, date Mark earlier to 40 CE from working backwards from Acts & Luke, which preserve theological significance for Jesus’ prediction of the second temple’s destruction and Gospel as “eye-witness” account of followers. Critique for those selected claims here and here ↩

-

More careful way of putting it is the earliest, traceable text, in which subsequent family of text descends from ↩

-

See page 177 of Misquoting Jesus ↩

-

Small protest for this line of thinking here, what is essential to the Christian faith (i.e. “Jesus died and his followers believed that he was resurrected”) is not synonymous to importance, as there’s a whole theological package to the Christian belief built on specific words/phrasings. The latter regards is in respect to what Christianity has already been developed into (i.e. Nicene Christianity), with differences brought from those alternative textual readings diluted along the history and in the popular mind ↩

-

See Acts 4:32-37 and Acts 2:44-46, granted that 1) the discipleship community was relatively small and tight-knit to allow for such egalitarian/altruistic practices 2) those very early followers likely also believed that the end of the world was imminent in their lifetime (i.e. establishment of God’s kingdom and Jesus second return) ↩