February 12th, the day after Andrew Yang dropped out of the presidential race, I remember running into the few friends who knew I was very involved in his campaign. Out of genuine concern, they asked how I felt about the news, to which I casually replied that it was a logical outcome I expected, given his disappointing finish in the Iowa and New Hampshire primary as well as his campaign’s poor economic circumstances at the time. But as I returned home and tried to resume my normal routine, my girlfriend noticed my unusual reticence and asked if I was okay. I knew my quietness probably came from a sense of disappointment that I was unwilling to express, though I believed that my unperturbed reaction to Yang’s exit was the appropriate response. However, as I confronted my own emotions, I realized that all the support I gave to Yang, the donations and phone banking, inadvertently grew as an offshoot from the conflicts I had with my father, who passed away unexpectedly three months prior. As his campaign came to its procedural end, it suddenly hit me that the closure with my dad, one that I was searching for through Yang’s campaign this whole time, also ended in permanence. Knowing that I lost him for the last time, I broke down.

Yang appealed to the nerdy software engineering demographic both my dad and I are from: he is witty, technologically literate, and unapologetically honest for problem-solving. I saw Yang as the conversational bridge that would create new opportunities for discussion with my dad regarding our generational differences as well as commonalities, since my dad usually does not share transparently about his political perspectives. But it was the topic of the intersection between work and value, one central to Yang’s entire platform, that touched me the most, as it defined the basis of tension underlying the exchanges with my dad throughout my time in college. Yang often alludes to our society’s collective mistake in seeing economic value and human value as one and the same. He argued that not only the various types of work that are valuable to a healthy, functional society, such as teaching, art, or local journalism, are undervalued and actively discouraged by our economic structure, people often helplessly tie their identity to their work and everything about their work; the failure to meet the standards of the job market, when viewed as an individual failure, easily becomes psychologically destructive. Personally, this confluence of economic and human value was reinforced deeply into my cognition by the scattered conversations with my dad and my time as an undergrad in computer science.

Perhaps my dad saw his engineering side in me, he had been rather intentional to push me towards software development ever since high school, oftentimes indirectly by suggesting how interesting he finds programming to be or sometimes directly by urging me to invest more time into it. Despite also taking interest in computers and enrolling in a computer science program, I was more inquisitive at the time about the origin and development of the religion I was indoctrinated in, which naturally gravitated me towards humanity subjects such as philosophy and history. My exposure then to the vast array of human thoughts left me with much anxiety about the cohabiting sympathy and antagonism towards my own upbringing and identity. But at the same time, I thought that studying about the nuanced evolution to the world of ideas was not just extremely helpful in being more self-aware but also beneficial to the fast-paced, ahistorical society that seems to be so insensitive to the nuance of culture and human thoughts. My fascination in humanity studies eventually seeped into the occasional conversations I had with my dad. He would always ask excitedly about the computer science classes I was in, and I would briefly talk about them but also slip in the interesting things I found from my history or philosophy courses. Perhaps out of ignorance or genuine disinterest in those subjects, he would quickly change the conversations to be about my programming job search. His silent indifference would often frustrate me, but to hide it, I would just jokingly blurt out my desire to be someone different, “maybe I want to be a historian or a philosopher.” This caught him with surprise at first, but as I indicated more about my seriousness in considering an alternative academic career in the humanity fields, our conversation would just quickly devolve into both sides defending what they perceive as valuable, with the major lingering point of tension essentially amounting to a simple concern:

How do those pursuits translate monetarily?

It wasn’t just the thought itself that bothered me, which by any means is very reasonable, but rather the presumed belief that a career is not worth pursuing if it does not generate enough capital. To my sensitive self then, his repeated advocacy for a programming career and unspoken dismissal towards my passion meant an invalidation of the studies I valued greatly, simply on the basis of their economic prospect.

Sympathizing with what he said is not something easy for me to do back then, as I was rather resentful towards him, but further reflection on his background has helped me recognize and accept his humanity. Like many other successful Chinese immigrants at the time, my dad grew up in poor conditions, excelled in GaoKao (the Chinese college entrance exam) to enter a prestigious university, came to the states for graduate school, and took up a stable software engineering job afterwards. Coming from his unique competitive times, as well as being the single breadwinner of the house, he was much attuned to a survival mindset, which in the context of modern society, is about securing a stable stream of income from an industry favored by the market; the adeptness at survival is characterized by how irreplaceable overall your skills are, which in turns translates to a certain market value. To such ends, the ultimate utility of a college education is only as good as the job it prepares for.

And those were the beliefs that were drilled deep into my subconscious, despite my emphatic aversion to the logic behind. Amidst my effort to branch out from computer science, those were the constant backdrops that lead to episodic self-questioning, not just about the bleak economic outlook and the over-saturated market of academia but the virtue of humanity studies themselves. Whatever progress, if there is even such a quantitative metric to judge progress in humanity, seems to be only meaningful in the private, cocooned world of erudite scholars, one that exists at best upon the fringe of this profit-driven society. On the other end, IT, as an entire industry, seems to have the capacity for endless potential, with people of diverse backgrounds swarming in to get a piece of the goldmine. The entrepreneurial tech culture is uplifted with the riveting tales of young geniuses who transformed their ideas into revolutionary products that permanently disrupted the market status-quo, and the only hindrances are one’s creativity, intellect, and perseverance. As someone who witnessed and secured his first bucket of gold from the height of the early dot-com bubble days, my dad spoke about the opportunities that programming creates under this light of exuberance; it is challenging and meaningful to build software. Better yet, the generous pay and benefits provide enough material comfort to never attend to the ugliness of poverty and survival needs.

Whether it was my competitiveness or hidden desire to reciprocate his excitement for technology, I adopted a high standard for myself, enrolling in many advanced computer science courses and being largely preoccupied with improving my engineering caliber. However, programming, or rather my perception of programming, increasingly became mentally taxing, as my attitude towards it gradually steered from the fun, genuine craftsmanship to a marketable asset I must hone constantly. Perhaps from the constant greeting of industry whenever I set foot into the CS department, the valuation of my acquired computer skills and knowledge has always been distinctly connected to the industry. Corporations would host weekly tech talks and workshops that aimed to increase their campus presence and help students, but I couldn’t help but see myself as part of a larger competition for human capital, as the speaker would regularly conclude the talks by taking resumes, followed by a line of students eager to network. In this light, my curiosity for knowledge from joining such talks was inevitably overshadowed by the perceived tone of competition, and my sense of identity was slowly directed towards fulfilling this functional role of being an outstanding coder. The anxiety culminated whenever the recruiting season started, as my daily schedule became bombarded by interview calls that seemed like an unending cycle of self-advertising and problem solving, and the rest of my time was dichotomized into school work and the improvement of my career profile. The more I invested myself into computer science, the more guilt I felt while reading the literature I enjoyed, since I was unwittingly convinced that it offered no practical utility. Yet in the face of my self-imposed coercion, philosophy and history offered me solace in the space of introspection that they provided, to momentarily withdraw from the mundanity of my immediate experiences, and to think freely on things outside of computer science that are of importance to human experiences; they were not just a reminder of the transient importance of my labor but were also the fleeting window for self-expression that I desperately needed.

Nonetheless, those realizations were only temporary, as my drive to obtain a respectable job led me to focus on the optimization of my market worth, even towards the last moments with my dad. He died from heart failure the day after our last conversation, and that conversation still surfaces vividly when I recall. As I was busy preparing for a final round interview that Sunday night, he called me, with an unusual fatigue and quietness in his voice. Unlike his usual conversation starter, he asked me about how I was feeling, knowing that I was going through a lot of interviews. Having just finished a coding question, I was replaying the solution in my head, so to tune out his existence on the other line, I just responded tersely, hoping to quickly end the conversation. Upon my silence, he paused for a moment, and murmured,

“很累吧…(it must be tiring).”

I did not reply.

In our mutual silence, I could sense that he wanted to keep the conversation going but was struggling to find the right words.

Annoyed by this apparent waste of time, I snapped, “我要走了 (I have to go).”

“嗯… (ok),” he reassured, “早点休息, 别搞太累了(try to sleep early, don’t stress yourself out).”

I hung up.

For a long time after his death, I was stuck in a weird loop, void of memory and sentiment towards any event that was happening, and I would often repeatedly refresh the Twitter page of Yang, only to regain a sense of traction to the world from the campaign that I was so used to following. I would often forget, even just now writing, what really made me so attached to humanity, to religion, to history, or to Yang, and I would forget this guilt, suppressed by a dehumanized view of my father, that it was my intense desire to optimize for my economic worth that lost my last chance to connect to him as a human being, to discuss our humanness besides all the fancy technology.

It was on that road that I lost my father.

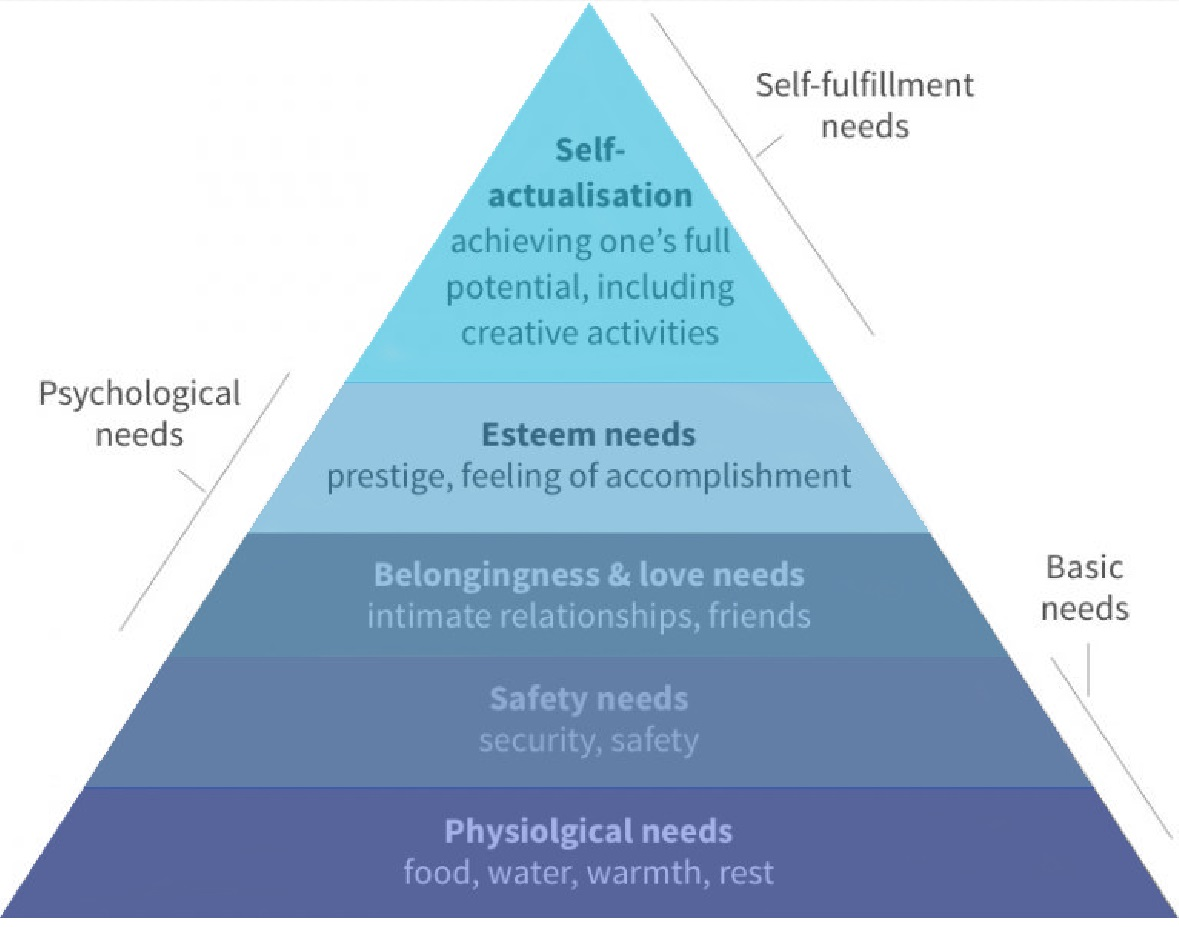

Although I could not fully explain back then to him why I valued humanity studies so much, having to touch the death of my father and reflect on my past four years made me understand something so painfully simple, that the concept of value is, at its core, personal and up to the individual to realize; it is relational and cannot be made sense of in the absence of our own perceptions. But in society, values are often structured and pushed from the top-down, in forms of GDP, stock market performance, or just the pay of our jobs. We partake in this distribution process by building cultures that value certain occupations over others. Especially in the one I grew up in, jobs are the ultimate token of societal membership, with its persuasive power hinged upon the cruel reality of hyper-competition over limited opportunities and resources. But what I came to realize is that although our survival needs are indisputably valuable, so are the many things in life that make surviving slightly more bearable in helping us to become more mentally resilient. This intuition to structure my needs or values in a hierarchical order of importance is inadequate because the needs among the hierarchies are much more interrelated and interactive, rather than the strict order of dependence suggested. For me, the need for a stable job does not simply do away the need for community or creative outlets, but the former inhibited me greatly from realizing the importance of the latter.

Deep down, however, this hierarchical way to view value came natural for me and possibly for my dad too because of the deep sense of scarcity in our respective lives. For him, it may have come from the deprivation of food and material comfort in his youth, so he was naturally oriented towards fulfilling those practical needs to sustain a family, and he subsequently viewed them to be more important and foundational. For me, it came from the absence of him in the large majority of my life, the absence of time together for meaningful conversations, and the absence of true recognition. It was such absence that made the notion of him ever so elusive to me. To fill this hollow, I built a towery image of him from the fragments of descriptions I could get from his friends and parents: loyal, energetic, intellectually gifted, hard-working, and responsible. I admired him, chased after his accomplishments, and lashed myself to try harder whenever I fell in order to narrow the gap from him. But there was a deeply buried part of me that just yearned to be understood, and I thought my competence in software engineering was just that last hurdle to cross, and once I crossed it, he would finally listen to me on equal terms. But just as I realized back then and now, he is not perfect, and there is as much that I need to understand about him as I wished he understood about me. I realize that my own worth and purpose was so intricately tied with his existence throughout my life, and I need to find a new way to move forward now. Because in the end, value is something that I have to find on my own.